Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Bill of Rights reading honors 'mayor of Franklin Street'

Chapel Hill Herald, Dec. 16, 2008

By LISA A. YOUNG

CHAPEL HILL -- With the traffic and activity of downtown Chapel Hill buzzing around them, a group of elected officials and local residents paused Monday to reflect on freedom and a man who championed it as they gathered for an annual reading of the Bill of Rights.

This year's event at Peace and Justice Plaza in front of the old Franklin Street post office -- organized by the Orange County Bill of Rights Defense Committee -- also served as a tribute to the late Joe Herzenberg, a former Chapel Hill councilman and the so-called "mayor of Franklin Street."

Herzenberg, who died last fall at the age of 66, was one of the first openly gay elected officials in the South and is particularly remembered for his passion for civil rights.

"We're doing this in honor of Joe," said State Sen. Ellie Kinnaird, who gave a few remarks before the reading. She then looked heavenward and added, "We know you're doing the right thing up there, too."

Bill of Rights Day 2008 marks the 217th anniversary of the day the necessary number of states ratified the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Kinnaird said the event has been held in downtown Chapel Hill for at least the last 20 years.

Chapel Hill Mayor Pro Tem Jim Ward, Orange County Commissioner Barry Jacobs and Carrboro Mayor Mark Chilton each read a proclamation declaring Dec. 15 "Bill of Rights Day" in their respective jurisdictions. They noted that North Carolina withheld its ratification of the Constitution until a Bill of Rights could be added.

All three jurisdictions have passed resolutions reaffirming the human and civil rights of residents. Additionally, Jacobs and Chilton said, the county and the Town of Carrboro have established policies against the use of local law enforcement to enforce civil immigration law and policy.

Reading with gusto

Ten individuals then read, some with great gusto, the original 10 constitutional amendments.

Daniel Pollitt, a retired UNC law professor who has been attending the Bill of Rights reading for most of its history, said he recalls a time when some had to read more than one amendment because there weren't enough people. This year's crowd of 15-20 people was much bigger than in years past, he said.

"It's good to keep people reminded that we have a Bill of Rights and they ought to abide by it," Pollitt added.

By LISA A. YOUNG

CHAPEL HILL -- With the traffic and activity of downtown Chapel Hill buzzing around them, a group of elected officials and local residents paused Monday to reflect on freedom and a man who championed it as they gathered for an annual reading of the Bill of Rights.

This year's event at Peace and Justice Plaza in front of the old Franklin Street post office -- organized by the Orange County Bill of Rights Defense Committee -- also served as a tribute to the late Joe Herzenberg, a former Chapel Hill councilman and the so-called "mayor of Franklin Street."

Herzenberg, who died last fall at the age of 66, was one of the first openly gay elected officials in the South and is particularly remembered for his passion for civil rights.

"We're doing this in honor of Joe," said State Sen. Ellie Kinnaird, who gave a few remarks before the reading. She then looked heavenward and added, "We know you're doing the right thing up there, too."

Bill of Rights Day 2008 marks the 217th anniversary of the day the necessary number of states ratified the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Kinnaird said the event has been held in downtown Chapel Hill for at least the last 20 years.

Chapel Hill Mayor Pro Tem Jim Ward, Orange County Commissioner Barry Jacobs and Carrboro Mayor Mark Chilton each read a proclamation declaring Dec. 15 "Bill of Rights Day" in their respective jurisdictions. They noted that North Carolina withheld its ratification of the Constitution until a Bill of Rights could be added.

All three jurisdictions have passed resolutions reaffirming the human and civil rights of residents. Additionally, Jacobs and Chilton said, the county and the Town of Carrboro have established policies against the use of local law enforcement to enforce civil immigration law and policy.

Reading with gusto

Ten individuals then read, some with great gusto, the original 10 constitutional amendments.

Daniel Pollitt, a retired UNC law professor who has been attending the Bill of Rights reading for most of its history, said he recalls a time when some had to read more than one amendment because there weren't enough people. This year's crowd of 15-20 people was much bigger than in years past, he said.

"It's good to keep people reminded that we have a Bill of Rights and they ought to abide by it," Pollitt added.

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

Bill of Rights Day 2008 press release

Orange Politics, Dec. 2, 2008

From Peggy Misch:

COMMEMORATION OF CIVIL AND HUMAN RIGHTS!

12 Noon, Monday, December 15, 2008

Bill of Rights Day

Peace and Justice Plaza, East Franklin and Henderson Streets, Chapel Hill

Proclamations read by two mayors and county commissioner; 10 amendments read by participants; words spoken by NC Senator Ellie Kinnaird remembering Joe Herzenberg for his dedication to civil rights

Orange County Bill of Rights Defense Committee

Information: 942-2535

From Peggy Misch:

COMMEMORATION OF CIVIL AND HUMAN RIGHTS!

12 Noon, Monday, December 15, 2008

Bill of Rights Day

Peace and Justice Plaza, East Franklin and Henderson Streets, Chapel Hill

Proclamations read by two mayors and county commissioner; 10 amendments read by participants; words spoken by NC Senator Ellie Kinnaird remembering Joe Herzenberg for his dedication to civil rights

Orange County Bill of Rights Defense Committee

Information: 942-2535

Monday, November 10, 2008

Chapel Hill may name trail for Herzenberg

N&O, Orange Chat, Nov. 10, 2008

by MARK SCHULTZ

The Greenways Commission and the Parks and Recreation Commission voted unanimously to jointly recommend at tonight's Town Council meeting that the town make the following naming and dedication change:

* Dedicate the future phase 3 section of the Bolin Creek Trail in honor of Joe Herzenberg. The commissions note Herzenberg was a strong proponent of open space and greenways and left at least $250,000 upon his death to be used for the Bolin Creek Trail. (The commissions also note that it would be easier to plan a memorial to Herzenberg if any such dedication were made prior to construction.)

by MARK SCHULTZ

The Greenways Commission and the Parks and Recreation Commission voted unanimously to jointly recommend at tonight's Town Council meeting that the town make the following naming and dedication change:

* Dedicate the future phase 3 section of the Bolin Creek Trail in honor of Joe Herzenberg. The commissions note Herzenberg was a strong proponent of open space and greenways and left at least $250,000 upon his death to be used for the Bolin Creek Trail. (The commissions also note that it would be easier to plan a memorial to Herzenberg if any such dedication were made prior to construction.)

Joe and Allan Gurganus at Joe's Stonewall party, 2004.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Helms and Herzenberg: When The Old South Met New

Huffington Post, Oct. 28, 2008

by ERIK OSE

Despite sharing the same initials and middle name "Alexander," Jesse Helms and Joe Herzenberg were very different. Helms was a bigoted, heterosexual, Southern Baptist, extreme right wing Republican who used divisive politics to keep himself in power for five U.S. Senate terms. Herzenberg was a tolerant, gay, Jewish, staunchly liberal Democrat who spent his life standing up for progressive ideals.

Jesse Helms and Joe Herzenberg

Yet they were both historic politicians who bookended the Old and New South. Helms, who died last summer at age 86, was the last unapologeticly racist politician of the segregation era. Herzenberg, who passed away one year ago today at age 66, was elected to the Chapel Hill Town Council two decades ago as the first openly gay elected official in the former Confederacy. And in 1984, their paths memorably crossed during the epic Helms-Hunt U.S. Senate race.

That year, Helms used shameful hate mongering against Herzenberg, his partner Lightning Brown, and the rest of North Carolina's gay and lesbian community to eke out his narrow re-election against sitting Gov. Jim Hunt. Helms had been getting decreasing mileage out of race-baiting, drawing heavy criticism for his filibuster against the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday a year earlier. So he found a new bogeyman - the homosexual menace.

Headlines screaming "Jim Hunt Is Sissy, Prissy, Girlish and Effeminate," and asking, "Is Jim Hunt homosexual?...Is he AC and DC?" appeared throughout 1984 in a free newspaper called The Landmark, a virulently anti-gay publication printed in Chatham County, N.C. The paper's homophobic publisher, Bob Windsor of Chapel Hill, was a cog in the Helms machine.

The stories ran alongside paid ads for Helms' re-election campaign, and hundreds of thousands of copies of the paper were distributed around the state, particularly in rural areas. Its press run increased dramatically in the weeks leading up to Election Day. The Landmark was funded by shadowy national Helms backers, part of the religious right that played a key behind-the-scenes organizing role in Helms' campaign.

That June, the N.C. Republican Party held a press conference to accuse Jim Hunt of a "gay connection" because gay donors had bought 100 of 700 tickets to a Hunt fundraiser in New York, and Sen. Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, leading Senate sponsor of a gay rights bill, had held a fundraising dinner for Hunt in Boston. The next day, Helms supporters paid to have a Landmark story reprinted as a large ad in the Raleigh News & Observer, accusing Hunt of "accepting a $79,000 contribution from Gay Activists."

Posing as reporters for the black and gay press, right-wing operatives made and taped phone calls to gay Hunt supporters around the country. Articles based on distorted excerpts from the phone calls were then published in issues of The Landmark.

Herzenberg and Brown were the smear campaign's N.C. poster children, targeted because they had helped co-found the Lesbian and Gay Democrats of North Carolina two years earlier, and were both vocally campaigning for Hunt. According to Lightning, one caller "asked about my fund raising for Hunt. The details ended up in The Landmark right away - it was frightening."

Besides running made-up stories that slandered Herzenberg and Brown relentlessly, including accusations that they had started a Chapel Hill NAMBLA (North American Man-Boy Love Association) chapter and were secretly "porno kings," The Landmark also published their home addresses and did everything possible to incite violence against the two of them. No wonder, as gay activist Mab Segrest recounted in an article on the Senate race, that "Brown and Herzenberg were subjected to more than a dozen separate incidents of intimidation, vandalism and harassment...for their work within the Democratic Party."

In a 1984 interview with the Independent Weekly when Herzenberg and Brown were awarded two of the Indy's first-ever Citizen Awards, Brown told of how "two people even threatened to kill me on Rosemary Street." Herzenberg called the attacks "very disruptive and at times painful." Asked if he had been scared, he admitted, with a subtlety that testified to his courage, "At moments."

In September, The Landmark published an interview with Helms in which he called homosexuality "a perversion and a crime." He described the gay movement as a "threat to the morals of our young people" and to "the ability of our population to reproduce itself...jeopardizing the very survival of the nation."

Helms was eventually forced to publicly distance himself from The Landmark after the paper published its most sensational charges accusing Jim Hunt of having a lover who was a "pretty young boy."" But he was well aware of how the paper was being widely distributed on his behalf. Helms betrayed himself on this point during a televised debate.

Although both were known in Triangle political circles, and in the state's gay community, the only actual media coverage of their status as gay activists was through The Landmark's smear campaign. But in one of their four debates, Helms twice gay-baited Hunt by thundering, "You're supported by people like Joe Herzenberg and Lightning Brown!" Herzenberg considered the moment he was publicly outed to have been when Helms announced his name on statewide television.

In the wake of his sliming by Helms' hateful tactics, Herzenberg decided he was out of the closet for good. His political activism and organizing flourished. He was elected as an openly gay Mondale delegate to the 1984 Democratic National Convention. He helped organize North Carolina's first Gay Pride Parade in 1986. He ran for the Chapel Hill Town Council as an openly gay candidate in 1985, and again in 1987 before he was finally elected.

Herzenberg was arguably the first gay candidate in U.S. history elected to office outside an urban area or historically gay enclave, and he did it by assembling a broad-based progressive coalition. His election was an important symbol of how the South was changing, and in some ways, Jesse Helms made it possible. Joe Herzenberg would have been thrilled to see the political landscape one year after his death, only one week away from the election of Barack Obama and a historic repudiation of the politics of division and hate.

by ERIK OSE

Despite sharing the same initials and middle name "Alexander," Jesse Helms and Joe Herzenberg were very different. Helms was a bigoted, heterosexual, Southern Baptist, extreme right wing Republican who used divisive politics to keep himself in power for five U.S. Senate terms. Herzenberg was a tolerant, gay, Jewish, staunchly liberal Democrat who spent his life standing up for progressive ideals.

Jesse Helms and Joe Herzenberg

Yet they were both historic politicians who bookended the Old and New South. Helms, who died last summer at age 86, was the last unapologeticly racist politician of the segregation era. Herzenberg, who passed away one year ago today at age 66, was elected to the Chapel Hill Town Council two decades ago as the first openly gay elected official in the former Confederacy. And in 1984, their paths memorably crossed during the epic Helms-Hunt U.S. Senate race.

That year, Helms used shameful hate mongering against Herzenberg, his partner Lightning Brown, and the rest of North Carolina's gay and lesbian community to eke out his narrow re-election against sitting Gov. Jim Hunt. Helms had been getting decreasing mileage out of race-baiting, drawing heavy criticism for his filibuster against the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday a year earlier. So he found a new bogeyman - the homosexual menace.

Headlines screaming "Jim Hunt Is Sissy, Prissy, Girlish and Effeminate," and asking, "Is Jim Hunt homosexual?...Is he AC and DC?" appeared throughout 1984 in a free newspaper called The Landmark, a virulently anti-gay publication printed in Chatham County, N.C. The paper's homophobic publisher, Bob Windsor of Chapel Hill, was a cog in the Helms machine.

The stories ran alongside paid ads for Helms' re-election campaign, and hundreds of thousands of copies of the paper were distributed around the state, particularly in rural areas. Its press run increased dramatically in the weeks leading up to Election Day. The Landmark was funded by shadowy national Helms backers, part of the religious right that played a key behind-the-scenes organizing role in Helms' campaign.

That June, the N.C. Republican Party held a press conference to accuse Jim Hunt of a "gay connection" because gay donors had bought 100 of 700 tickets to a Hunt fundraiser in New York, and Sen. Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, leading Senate sponsor of a gay rights bill, had held a fundraising dinner for Hunt in Boston. The next day, Helms supporters paid to have a Landmark story reprinted as a large ad in the Raleigh News & Observer, accusing Hunt of "accepting a $79,000 contribution from Gay Activists."

Posing as reporters for the black and gay press, right-wing operatives made and taped phone calls to gay Hunt supporters around the country. Articles based on distorted excerpts from the phone calls were then published in issues of The Landmark.

Herzenberg and Brown were the smear campaign's N.C. poster children, targeted because they had helped co-found the Lesbian and Gay Democrats of North Carolina two years earlier, and were both vocally campaigning for Hunt. According to Lightning, one caller "asked about my fund raising for Hunt. The details ended up in The Landmark right away - it was frightening."

Besides running made-up stories that slandered Herzenberg and Brown relentlessly, including accusations that they had started a Chapel Hill NAMBLA (North American Man-Boy Love Association) chapter and were secretly "porno kings," The Landmark also published their home addresses and did everything possible to incite violence against the two of them. No wonder, as gay activist Mab Segrest recounted in an article on the Senate race, that "Brown and Herzenberg were subjected to more than a dozen separate incidents of intimidation, vandalism and harassment...for their work within the Democratic Party."

In a 1984 interview with the Independent Weekly when Herzenberg and Brown were awarded two of the Indy's first-ever Citizen Awards, Brown told of how "two people even threatened to kill me on Rosemary Street." Herzenberg called the attacks "very disruptive and at times painful." Asked if he had been scared, he admitted, with a subtlety that testified to his courage, "At moments."

In September, The Landmark published an interview with Helms in which he called homosexuality "a perversion and a crime." He described the gay movement as a "threat to the morals of our young people" and to "the ability of our population to reproduce itself...jeopardizing the very survival of the nation."

Helms was eventually forced to publicly distance himself from The Landmark after the paper published its most sensational charges accusing Jim Hunt of having a lover who was a "pretty young boy."" But he was well aware of how the paper was being widely distributed on his behalf. Helms betrayed himself on this point during a televised debate.

Although both were known in Triangle political circles, and in the state's gay community, the only actual media coverage of their status as gay activists was through The Landmark's smear campaign. But in one of their four debates, Helms twice gay-baited Hunt by thundering, "You're supported by people like Joe Herzenberg and Lightning Brown!" Herzenberg considered the moment he was publicly outed to have been when Helms announced his name on statewide television.

In the wake of his sliming by Helms' hateful tactics, Herzenberg decided he was out of the closet for good. His political activism and organizing flourished. He was elected as an openly gay Mondale delegate to the 1984 Democratic National Convention. He helped organize North Carolina's first Gay Pride Parade in 1986. He ran for the Chapel Hill Town Council as an openly gay candidate in 1985, and again in 1987 before he was finally elected.

Herzenberg was arguably the first gay candidate in U.S. history elected to office outside an urban area or historically gay enclave, and he did it by assembling a broad-based progressive coalition. His election was an important symbol of how the South was changing, and in some ways, Jesse Helms made it possible. Joe Herzenberg would have been thrilled to see the political landscape one year after his death, only one week away from the election of Barack Obama and a historic repudiation of the politics of division and hate.

Saturday, October 11, 2008

Joe Herzenberg's Yahrzeit

As the anniversary of Joe Herzenberg’s death nears I would like to share with you the Jewish custom for observing the Yahrzeit of a family member. The Hebrew Date is used instead of the actual date of death. This year the date will be November 14.

Traditionally family members mark the yearly anniversary of a death (called "yahrtzeit") in two ways:

Light a yahrizeit candle. A candle that burns for 24 hrs. Yahrzeit candles should be lit the evening before the date specified. This is because the Jewish day actually begins at sundown on the previous night. There is no prayer said with this lighting.

And giving some form of charity (tzedakah) in the name of the deceased.

Candles can be purchased at Harris Teeter in the ethnic section of the store or at the Chapel Hill Kehillah gift shop.

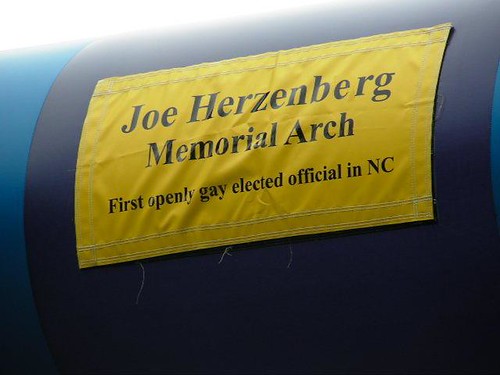

I gave a Rainbow Arch to NC Pride Fest that is now is the Joe Herzenberg Memorial Arch. It was dedicated September 26 at the Pride March in Durham.

Joe left 1/2 of his estate equally to Friends of Chapel Hill Parks and Recreation and Greenways for the Bolin Creek Greenway, especially for benches and other amenities, as well as actual construction; and the Inter-Faith Council for Social Services, Inc. for the operations of the homeless shelter and the kitchen. Each has received a check in the amount of $250,000.00.

L’shalom,

Kathie Young

Traditionally family members mark the yearly anniversary of a death (called "yahrtzeit") in two ways:

Light a yahrizeit candle. A candle that burns for 24 hrs. Yahrzeit candles should be lit the evening before the date specified. This is because the Jewish day actually begins at sundown on the previous night. There is no prayer said with this lighting.

And giving some form of charity (tzedakah) in the name of the deceased.

Candles can be purchased at Harris Teeter in the ethnic section of the store or at the Chapel Hill Kehillah gift shop.

I gave a Rainbow Arch to NC Pride Fest that is now is the Joe Herzenberg Memorial Arch. It was dedicated September 26 at the Pride March in Durham.

Joe left 1/2 of his estate equally to Friends of Chapel Hill Parks and Recreation and Greenways for the Bolin Creek Greenway, especially for benches and other amenities, as well as actual construction; and the Inter-Faith Council for Social Services, Inc. for the operations of the homeless shelter and the kitchen. Each has received a check in the amount of $250,000.00.

L’shalom,

Kathie Young

Sunday, September 28, 2008

Gay Pride allies pin their hopes on Obama

N&O, Sept. 28, 2008

by Jesse James DeConto

DURHAM - "We are on the doorstep of the most important political election of our day," Chapel Hill Town Council member Mark Kleinschmidt told the crowd (at the N.C. Pride Festival on Saturday) on Duke's East Campus.

...

Kleinschmidt and others celebrated the late Chapel Hill Town Council member Joe Herzenberg, who in 1987 became the first openly gay elected official in North Carolina. The path to the stage passed beneath a 20-foot-high inflated arch -- the Rainbow Memorial Arch -- in Herzenberg's honor. He died in October.

"His election opened the door for the rest of us who followed," said Orange County Commissioner Mike Nelson, former mayor of Carrboro.

by Jesse James DeConto

DURHAM - "We are on the doorstep of the most important political election of our day," Chapel Hill Town Council member Mark Kleinschmidt told the crowd (at the N.C. Pride Festival on Saturday) on Duke's East Campus.

...

Kleinschmidt and others celebrated the late Chapel Hill Town Council member Joe Herzenberg, who in 1987 became the first openly gay elected official in North Carolina. The path to the stage passed beneath a 20-foot-high inflated arch -- the Rainbow Memorial Arch -- in Herzenberg's honor. He died in October.

"His election opened the door for the rest of us who followed," said Orange County Commissioner Mike Nelson, former mayor of Carrboro.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Helms created our ‘Stonewall’: N.C. Senate Vote 90 was a defining moment for queer N.C.

Q-Notes, July 26, 2008

By DAVID STOUT

Mandy Carter leaps onto the comparison like a cat pouncing on a cricket. “Yes, I so agree,” she says excitedly. “That was a defining moment for the lesbian and gay community in North Carolina. I think you absolutely can call it this state’s version of Stonewall.”

The event Carter is referring to is the creation and year-long organizing of N.C. Senate Vote 90, a statewide political campaign founded by a handful of Triangle-area lesbians and gay men for the purpose of defeating virulently anti-gay Sen. Jesse Helms. The Republican senator from North Carolina was seeking his fourth term in the 1990 general election.

“We were all upset about Helms’ gay record,” Carter observes. “But as a black lesbian I was also very aware of his horrible record on civil rights. Even George Wallace and Strom Thurmond understood that things were changing, but Helms was not letting go. Let’s not forget that he was an equal opportunity destroyer.”

Anyone who even halfheartedly follows politics already knows that Helms was reelected. What many don’t know, however, is that some of the most significant gains won by the state’s LGBT community in the ensuing two and a half decades have risen from the ashes of NCSV90’s stinging defeat.

The advances haven’t come from the loss itself — the crucial exception being the unavoidable and unavoidably empowering realization that the LGBT community could have its collective breath knocked out on Tuesday and still get up on its feet on Wednesday. Rather, the gains have blossomed from the lessons learned, the groundwork laid and the coalitions assembled before the polling places even opened that fateful election day.

“This all really begins with Sue Hyde,” Carter recalls. “It was around 1989 and she was working for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. She was in Durham for a hearing because the City Council was considering a gay anti-discrimination policy. Afterward, she asked a few of us what we were going to do about Jesse Helms.”

Hyde’s deceptively simple question sparked a house meeting of local activists, including host David Jones, Carter, openly gay Chapel Hill Town Council member Joe Herzenberg, Mab Segrest, Jim Duley, Jim Baxter and Meredith Emmett.

“We needed to do something, but we didn’t know what,” Carter says. “We didn’t know anything about what we were doing.” Still, there was enough energy and determination in that initial meeting to convince Carter to tell her bosses at Durham’s legendary women’s music label Ladyslipper that she was “going to take time off to work on this thing to defeat Helms.”

Carter, a nationally respected activist who started organizing with the War Resister’s League in the late ’60s in San Francisco, wound up campaign manager of the nebulous start-up, which after a bit of research was registered with the Federal Elections Commission as an independent expenditure political action committee.

“That meant we could raise and spend as much as we wanted, but we could have no contact with the Gantt campaign,” explains Carter.

Harvey Gantt, the African-American former mayor of Charlotte, was creating history with his bid for Helms’ seat. No black candidate had ever before run for the U.S. Senate in North Carolina and Gantt was actually making a strong showing in the early polling.

NCSV90’s launch was less auspicious. The group had an office but no money. Carter, at that point a full-time volunteer, says things turned around as word of the campaign spread.

“We had people contacting us from Greensboro, Charlotte, Asheville, Wilmington asking ‘how can I get involved?’ When we saw that, we decided it was time to go public in the traditional press. The response was incredible, and that’s when we knew we had something. Money started pouring in from our friends outside North Carolina. It was just remarkable.”

The PAC was now legitimately up and running, but organizers knew that money alone didn’t equal victory. It would take more than paid staff and media buys to defeat the Helms juggernaut. To maximize the odds of victory, they needed a voter army.

So, they assembled one — and forever changed the face of North Carolina politics.

“We had a strategy meeting in Chapel Hill where we were wondering how we would pull together enough votes to defeat Helms,” Carter remembers. “Even if we got every gay person to vote we figured it wouldn’t be enough. We started to think, who would work with us on this? That led us to get a copy of Helms’ voting record.

“Arts, environment, education, people of color, gay and lesbian allies, pro-choice — these were the groups we knew we should be in contact with. It was an alliance that we needed then and I’m happy to say that it still exists to this day. That historic moment really got down to the roots of who would be the progressive coalition in North Carolina.”

As the race — one of the most closely watched in the nation — unfolded through the spring and summer, NCSV90 volunteers statewide worked tirelessly canvassing neighborhoods, staffing phone banks, fundraising and registering voters. Gantt’s numbers continued to grow until he was actually leading in the polls.

And then the wheels fell off. In an 11th hour act of desperation, Helms’ campaign unleashed what has come to be known as simply “The Ad.”

The TV spot focused on a white man’s hands as he tore up a rejection notice for a job that, according to a voiceover, was given to a less qualified minority applicant “because of a racial quota.” The ad was blasted by moderate and left-wing pundits and politicians nationwide for its racist fear-mongering. But, Helms was unbowed and the spot stayed on the air.

A few weeks later, the embattled incumbent eeked out a win with 52.5 percent of the vote. It was a crushing loss for North Carolina’s LGBT community and the entire progressive coalition after they had worked so hard and come so very close.

“I was taping every ad during the campaign,” Carter says. “When I saw that one, I said this election’s over. But it still didn’t soften the blow because we had experienced all these mini victories — money, volunteers, this amazing alliance we had put together — along the way. To lose like that at the end was devastating.”

Today, the river of time has carved out enough emotional distance that the perspective required to accurately assess NCSV90’s “failure” is possible.

Beyond the progressive coalition that was established, other essential, lasting benefits from the campaign include EqualityNC — the statewide LGBT advocacy organization was founded as NC Pride PAC by key Senate Vote 90 organizers — as well as an increase in the number of openly gay elected or appointed officials in the state.

A couple of years after working with NCSV90, Mike Nelson successfully ran for the Carrboro Board of Aldermen. After serving just one term, in 1995 he became the first openly gay candidate to be elected mayor of a North Carolina city. Mark Kleinschmidt and Julia Boseman are additional out candidates who successfully campaigned for public office.

Amazingly, nearly three decades after the fact, one more advancement from the anti-Helms campaign is playing out before us right now, in the historic political race of another trailblazing African-American politician — this one seeking the nation’s highest office.

Presidential candidate Sen. Barack Obama’s primary victory and competitive general election polling in North Carolina is a testament to the courage of Harvey Gantt and the sweeping vision of a few gays and lesbians at a house party who were very early adopters of the real politics of change.

Looking at these results, it’s clear that the legacy of NCSV90 actually has little to do with loss or lack, but a great deal to do with increased common will, visibility, political standing and connectedness. The campaign ushered in a new era for LGBT North Carolinians. It should be celebrated for the remarkable victory history has revealed it to be.

“Helms has come and gone,” Carter concludes, speaking pensively. “But we’re still here, and in the long run we won.”

By DAVID STOUT

Mandy Carter leaps onto the comparison like a cat pouncing on a cricket. “Yes, I so agree,” she says excitedly. “That was a defining moment for the lesbian and gay community in North Carolina. I think you absolutely can call it this state’s version of Stonewall.”

The event Carter is referring to is the creation and year-long organizing of N.C. Senate Vote 90, a statewide political campaign founded by a handful of Triangle-area lesbians and gay men for the purpose of defeating virulently anti-gay Sen. Jesse Helms. The Republican senator from North Carolina was seeking his fourth term in the 1990 general election.

“We were all upset about Helms’ gay record,” Carter observes. “But as a black lesbian I was also very aware of his horrible record on civil rights. Even George Wallace and Strom Thurmond understood that things were changing, but Helms was not letting go. Let’s not forget that he was an equal opportunity destroyer.”

Anyone who even halfheartedly follows politics already knows that Helms was reelected. What many don’t know, however, is that some of the most significant gains won by the state’s LGBT community in the ensuing two and a half decades have risen from the ashes of NCSV90’s stinging defeat.

The advances haven’t come from the loss itself — the crucial exception being the unavoidable and unavoidably empowering realization that the LGBT community could have its collective breath knocked out on Tuesday and still get up on its feet on Wednesday. Rather, the gains have blossomed from the lessons learned, the groundwork laid and the coalitions assembled before the polling places even opened that fateful election day.

“This all really begins with Sue Hyde,” Carter recalls. “It was around 1989 and she was working for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. She was in Durham for a hearing because the City Council was considering a gay anti-discrimination policy. Afterward, she asked a few of us what we were going to do about Jesse Helms.”

Hyde’s deceptively simple question sparked a house meeting of local activists, including host David Jones, Carter, openly gay Chapel Hill Town Council member Joe Herzenberg, Mab Segrest, Jim Duley, Jim Baxter and Meredith Emmett.

“We needed to do something, but we didn’t know what,” Carter says. “We didn’t know anything about what we were doing.” Still, there was enough energy and determination in that initial meeting to convince Carter to tell her bosses at Durham’s legendary women’s music label Ladyslipper that she was “going to take time off to work on this thing to defeat Helms.”

Carter, a nationally respected activist who started organizing with the War Resister’s League in the late ’60s in San Francisco, wound up campaign manager of the nebulous start-up, which after a bit of research was registered with the Federal Elections Commission as an independent expenditure political action committee.

“That meant we could raise and spend as much as we wanted, but we could have no contact with the Gantt campaign,” explains Carter.

Harvey Gantt, the African-American former mayor of Charlotte, was creating history with his bid for Helms’ seat. No black candidate had ever before run for the U.S. Senate in North Carolina and Gantt was actually making a strong showing in the early polling.

NCSV90’s launch was less auspicious. The group had an office but no money. Carter, at that point a full-time volunteer, says things turned around as word of the campaign spread.

“We had people contacting us from Greensboro, Charlotte, Asheville, Wilmington asking ‘how can I get involved?’ When we saw that, we decided it was time to go public in the traditional press. The response was incredible, and that’s when we knew we had something. Money started pouring in from our friends outside North Carolina. It was just remarkable.”

The PAC was now legitimately up and running, but organizers knew that money alone didn’t equal victory. It would take more than paid staff and media buys to defeat the Helms juggernaut. To maximize the odds of victory, they needed a voter army.

So, they assembled one — and forever changed the face of North Carolina politics.

“We had a strategy meeting in Chapel Hill where we were wondering how we would pull together enough votes to defeat Helms,” Carter remembers. “Even if we got every gay person to vote we figured it wouldn’t be enough. We started to think, who would work with us on this? That led us to get a copy of Helms’ voting record.

“Arts, environment, education, people of color, gay and lesbian allies, pro-choice — these were the groups we knew we should be in contact with. It was an alliance that we needed then and I’m happy to say that it still exists to this day. That historic moment really got down to the roots of who would be the progressive coalition in North Carolina.”

As the race — one of the most closely watched in the nation — unfolded through the spring and summer, NCSV90 volunteers statewide worked tirelessly canvassing neighborhoods, staffing phone banks, fundraising and registering voters. Gantt’s numbers continued to grow until he was actually leading in the polls.

And then the wheels fell off. In an 11th hour act of desperation, Helms’ campaign unleashed what has come to be known as simply “The Ad.”

The TV spot focused on a white man’s hands as he tore up a rejection notice for a job that, according to a voiceover, was given to a less qualified minority applicant “because of a racial quota.” The ad was blasted by moderate and left-wing pundits and politicians nationwide for its racist fear-mongering. But, Helms was unbowed and the spot stayed on the air.

A few weeks later, the embattled incumbent eeked out a win with 52.5 percent of the vote. It was a crushing loss for North Carolina’s LGBT community and the entire progressive coalition after they had worked so hard and come so very close.

“I was taping every ad during the campaign,” Carter says. “When I saw that one, I said this election’s over. But it still didn’t soften the blow because we had experienced all these mini victories — money, volunteers, this amazing alliance we had put together — along the way. To lose like that at the end was devastating.”

Today, the river of time has carved out enough emotional distance that the perspective required to accurately assess NCSV90’s “failure” is possible.

Beyond the progressive coalition that was established, other essential, lasting benefits from the campaign include EqualityNC — the statewide LGBT advocacy organization was founded as NC Pride PAC by key Senate Vote 90 organizers — as well as an increase in the number of openly gay elected or appointed officials in the state.

A couple of years after working with NCSV90, Mike Nelson successfully ran for the Carrboro Board of Aldermen. After serving just one term, in 1995 he became the first openly gay candidate to be elected mayor of a North Carolina city. Mark Kleinschmidt and Julia Boseman are additional out candidates who successfully campaigned for public office.

Amazingly, nearly three decades after the fact, one more advancement from the anti-Helms campaign is playing out before us right now, in the historic political race of another trailblazing African-American politician — this one seeking the nation’s highest office.

Presidential candidate Sen. Barack Obama’s primary victory and competitive general election polling in North Carolina is a testament to the courage of Harvey Gantt and the sweeping vision of a few gays and lesbians at a house party who were very early adopters of the real politics of change.

Looking at these results, it’s clear that the legacy of NCSV90 actually has little to do with loss or lack, but a great deal to do with increased common will, visibility, political standing and connectedness. The campaign ushered in a new era for LGBT North Carolinians. It should be celebrated for the remarkable victory history has revealed it to be.

“Helms has come and gone,” Carter concludes, speaking pensively. “But we’re still here, and in the long run we won.”

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Brilliant Flight - a love poem for Mama Nayo and Joe (VIDEO)

This video honors the lives of Joe and Nayo Barbara Malcolm Watkins ("Mama Nayo"), a Durham community activist and educator who died of cancer on January 22, 2008. It was created by artist and poet Ebony Noelle Golden.

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Blacks added to plaza names: Marker naming rights leaders will be installed in the fall

Chapel Hill News, May 25, 2008

By Meiling Arounnarath

CHAPEL HILL -- The names of the first people approved for the town's new historical marker were all white. Where were the black people who helped lead the civil rights struggle in Chapel Hill, the local NAACP asked.

The NAACP recently recommended four additional names be added to the sidewalk marker planned for the Peace and Justice Plaza outside the Franklin Street post office. The Chapel Hill Town Council wants to install the marker in the fall.

The Naming Committee originally approved Joe and Lucy Straley, Charlotte Adams and Joe Herzenberg, who were active in the local peace and civil rights movements and other causes.

The NAACP proposed Henry "Hank" Anderson III, James R. Brittain, Hubert Robinson and Gloria Williams.

...

The historical marker will be a tablet installed in front of the flagpole.

It will read: "Peace and Justice Plaza" at the top. Under that will be the names of the nine honored, in alphabetical order, said Town Council member Sally Greene, who sits on the Naming Committee. More names can be added later.

"Most of them are probably not as well-known as these other activists because, as someone has said recently, the black community tends to be invisible and overlooked," Yonni Chapman, a local civil rights historian, told the Town Council. "The NAACP, upon hearing the news of this initiative to honor peace and justice activists, certainly supported the names put forward, but we thought it would be appropriate to have some African-Americans added to that list."

The Peace and Justice Plaza wasn't just a focus of the anti-war movement, Chapman said.

"It was also the focal point of the civil rights movement, of all the Martin Luther King Jr. marches that have been held," he said. "It's been a rallying area for the black freedom struggle in Chapel Hill, which has been tremendously important to this entire community."

By Meiling Arounnarath

CHAPEL HILL -- The names of the first people approved for the town's new historical marker were all white. Where were the black people who helped lead the civil rights struggle in Chapel Hill, the local NAACP asked.

The NAACP recently recommended four additional names be added to the sidewalk marker planned for the Peace and Justice Plaza outside the Franklin Street post office. The Chapel Hill Town Council wants to install the marker in the fall.

The Naming Committee originally approved Joe and Lucy Straley, Charlotte Adams and Joe Herzenberg, who were active in the local peace and civil rights movements and other causes.

The NAACP proposed Henry "Hank" Anderson III, James R. Brittain, Hubert Robinson and Gloria Williams.

...

The historical marker will be a tablet installed in front of the flagpole.

It will read: "Peace and Justice Plaza" at the top. Under that will be the names of the nine honored, in alphabetical order, said Town Council member Sally Greene, who sits on the Naming Committee. More names can be added later.

"Most of them are probably not as well-known as these other activists because, as someone has said recently, the black community tends to be invisible and overlooked," Yonni Chapman, a local civil rights historian, told the Town Council. "The NAACP, upon hearing the news of this initiative to honor peace and justice activists, certainly supported the names put forward, but we thought it would be appropriate to have some African-Americans added to that list."

The Peace and Justice Plaza wasn't just a focus of the anti-war movement, Chapman said.

"It was also the focal point of the civil rights movement, of all the Martin Luther King Jr. marches that have been held," he said. "It's been a rallying area for the black freedom struggle in Chapel Hill, which has been tremendously important to this entire community."

Friday, May 2, 2008

First names proposed for post office plaza

N&O, Orange Chat, May 2, 2008

by MARK SCHULTZ

The Chapel Hill Town Council will consider the first names to be engraved on a marker outside the Franklin Street post office on Monday.

The council voted in 2006 to name the spot the "Peace and Justice Plaza" in recognition of the political gatherings that have taken place there.

In a 2007 story, we reported that the the council voted to engrave the names of longtime activists Charlotte Adams and Joe and Lucy Straley on a 5 foot by 5 foot granite marker outside the post office.

Now comes word, by way of Monday's Town Council agenda, that town leaders have decided to add some other names to the marker.

The council will consider a recommendation to engrave the following names: Joe and Lucy Straley, Charlotte Adams, Joe Herzenberg, Hubert Robinson, James R. Brittain, Henry "Hank" Anderson III, and Gloria Williams.

by MARK SCHULTZ

The Chapel Hill Town Council will consider the first names to be engraved on a marker outside the Franklin Street post office on Monday.

The council voted in 2006 to name the spot the "Peace and Justice Plaza" in recognition of the political gatherings that have taken place there.

In a 2007 story, we reported that the the council voted to engrave the names of longtime activists Charlotte Adams and Joe and Lucy Straley on a 5 foot by 5 foot granite marker outside the post office.

Now comes word, by way of Monday's Town Council agenda, that town leaders have decided to add some other names to the marker.

The council will consider a recommendation to engrave the following names: Joe and Lucy Straley, Charlotte Adams, Joe Herzenberg, Hubert Robinson, James R. Brittain, Henry "Hank" Anderson III, and Gloria Williams.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)